Hatsuko Mary Higuchi

- Poston Preservation

- Jun 16, 2019

- 2 min read

Updated: Oct 24, 2019

My name is Hatsuko Mary Higuchi. I was born in Los Angeles 1939 on the eve of WWII. Executive Order 9066 destroyed my family’s life. We were sent to Poston, Arizona, a concentration camp on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. When we arrived we saw rows and rows of black tarred paper barracks surrounded by barred wires. Soldiers with guns. After the war ended, we returned with nothing except my parents determination to rebuild our lives.

Years later, I took my mother to Poston, came home and did a painting of guard towers and barrack and I asked her what she thought. Her expression turn to great sadness. She said in camp not a day went by was I wondering what would happen to my children. What will become of them.

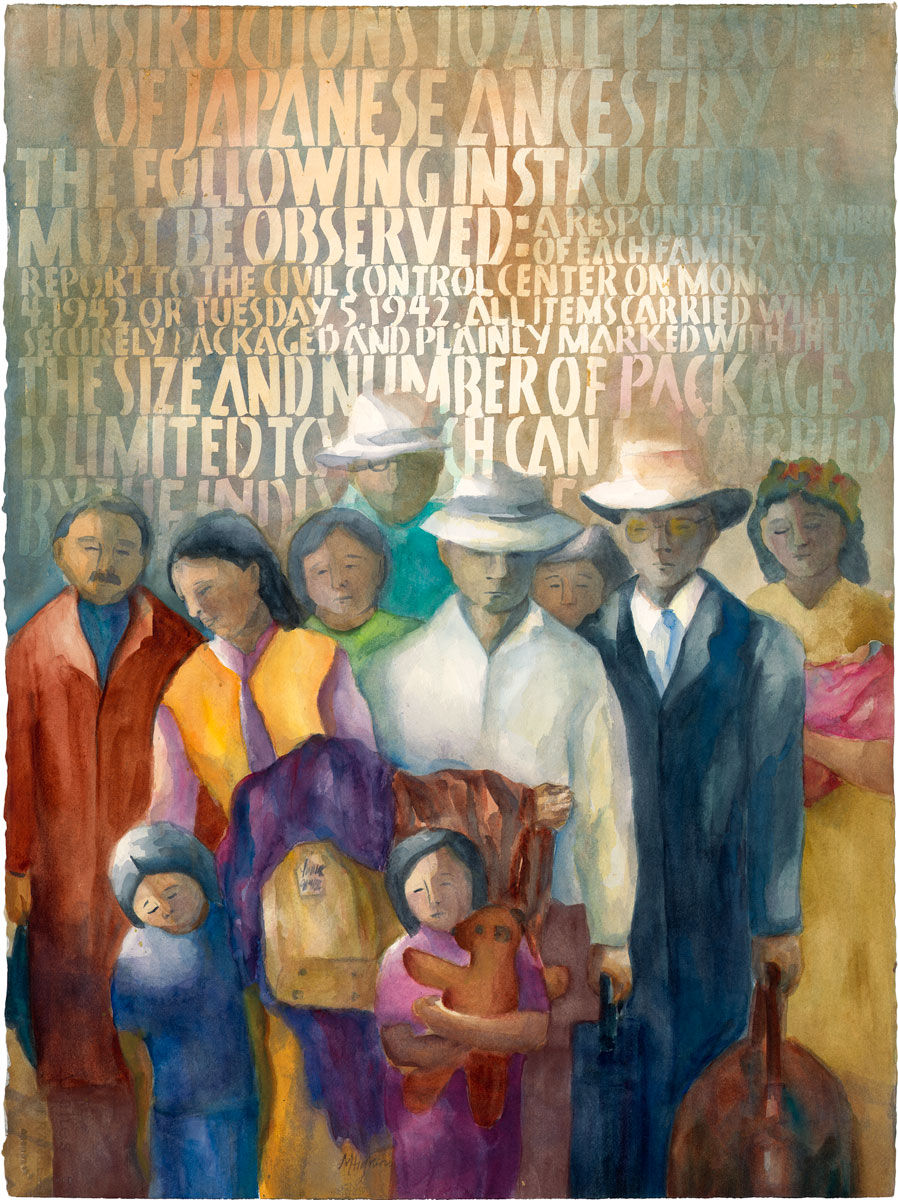

Hatsuko Mary Higuchi paints a variety of themes such as landscapes, figures, and abstracts. She uses watercolor, acrylic, mixed media, collage, and calligraphy. Her EO 9066 paintings depict faces with anonymous features or none at all, symbolizing the mass anonymity to which over 110,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry were reduced–denied due process and judged guilty solely by reason of their race. Mary Higuchi’s haunting portraits are a warning that what happened to Japanese Americans is a precedent for similar actions against other groups, unless we remember the lessons of the past.

E.O. 9066, Series 31. Woebegone. I looked up "woebegone" in the dictionary and it means exhibiting woe, sorrow, or misery; also dismal, desolate. This little girl, surrounded by luggage and her parents, looks lost, alone and uncertain about her future. The little girl was painted from a photo of my mother when she was sent to Japan after she was orphaned at the age of three.

E.O. 9066, Series 29. Unfinished Business: Hardship and Suffering, depicts the systematic destruction of the Nikkei family unit during the forced removal and incarceration. Families lost most of their personal possessions as they were forced to remote areas, then released after the war to start a new life from scratch. Parents lost control of the family. The long hours of work to rebuild their lives after the war took a toll on male heads of households. My father died at the age of 45, a few years after being released from the concentration camp. Studies have shown that 40% of Nikkei males incarcerated during the war, died before they reached the age of 60.

Comments